Tapestries-7 | What a time to be alive

We’re having the wrong conversation about venture.

Photo by Johannes Plenio

I believe today is the greatest time in history to be a consumer. For a growing number of us, not only is our economy available on-demand, but more than that, we are told that we deserve it this way.

It is our right to have four rolls of toilet paper delivered to our door tomorrow, to get a crosstown ride in NYC traffic for $6.49 or to get the entire catalogue of most TV series known to mankind for $11.99 a month. Product or service delivery that doesn’t measure up to these standards is railed against. “Legacy” is a dirty word.

This construct is borne out of the collision of technology and customer-centric business models. The result is…. really customer-centric businesses. Those of you who don’t share the distinction of calling yourself a ‘millennial’ love opining on what it is that makes us ‘tick’ or what it is that we want. You consistently miss the mark, but one thing you have (finally) gotten right is our view on asset ownership.

Yes, we are not interested in owning assets like you, but we absolutely demand the right to use those assets as if they are our own. Houses, cars, office space, music, film, vacation rentals — we want to use them all, we just don’t want to front the money generally required to own them. We demand the benefits of asset ownership without fully paying for them.

As it turns out, it may be that some enterprises that place customers at the absolute centre of their businesses, don’t turn out to be good ‘businesses’. We generally define a good business as one where you produce a good or service for less than the sale price of that good or service, or at least have the realistic potential to do so in the future.

The vast majority of the companies delivering these services (e.g. Uber, WeWork, Spotify etc.) are in no danger of turning a profit in the near future. In the pursuit of extreme growth with structurally unprofitable products (at least for now), they have burned a lot of cash. The ~dozen unicorns headed (or likely to head to) IPO this year, posted combined losses of $14bn last year and cumulative losses of $47bn.

Those are real losses and amount to a monumental pile of cash on fire. This funding gap is effectively money being thrown at consumers in the form of a subsidy. It is largely funded by venture capital funds and their investors: institutional investors, mutual funds and sovereign wealth funds.

The extreme losses sustained by these businesses may be a signal that asset owners demand a premium that consumers are not willing to pay. The owners of real assets (logistics providers, vacation rentals, office buildings, motor vehicles) and intangible assets (music, film, TV) have made clear what it costs to lease their assets. Customers are also relatively clear on what they’re willing to pay for said services.

Ultimately, there exists a gap between the two — represented by magnitude of the per-unit loss — which is being filled by venture capital. The thesis is generally that once these companies own enough of their respective markets, they’ll be able to raise prices to more adequately cover costs incurred. It remains to be seen whether customers will hang around when switching costs are low.

A lot of the businesses coming to market acknowledge that they may be structurally unprofitable (why is a question for another post). If they may never make money and are now subject to the scrutiny and MTM of public markets, there’s a large probability that the value of their enterprises may sink well below their latest private rounds. LYFT is currently trading ~40% below its listing price; UBER went public at a valuation of $70 billion (well below its anticipated $120bn valuation) and is now trading ~30% below its listing price.

With this context and the IPO rush upon us, it is an important time for reflection, to understand the system in which we are witnessing these trends.

To understand a system, look for the incentives.

Despite the concerns (both public and private) relating to these companies’ business models and propensity for burning enormous amounts of capital, they continued to operate in an environment of almost suspended belief, whereby the risks are apparent but the ability to raise further and large amounts of capital has been unconstrained. It has forced me to ask myself whether I fundamentally misunderstand the dynamic and asset class, or whether there’s something more non-obvious to understand.

The stakeholders involved in these businesses and their listings are not idiots: founders, early employees, investors (VC, late-stage growth equity) and underwriters. My current view, explored below, is that these people have the best grasp of the incentives inherent in the system in which they play and are extracting maximum benefits from them.

To understand this paradigm, we need to start thinking about companies’ evolution from start-up to mature business as a method of value creation within a broader system. We are stuck thinking about entrepreneurialism in reference to good and bad ideas, useful or useless products, right and wrong business models. Only once we start thinking in terms of winners and losers, will we understand the system in which we’re operating.

The Amazon Delusion

The aforementioned not-stupid people project an air of evangelism. Growth has become divine and is pursued at all costs. It is to be venerated, to the point that we must now “believe” in a company, not assess it in a dispassionate, profit-driven manner. This mindset, and its implicit disregard for costs (financial and non-financial) and financial discipline, is built on the premise that once a particular company grows to the point where it wields market dominance, it can raise prices to a level that will sustain the enterprise as a real business, not a thesis.

Amazon is often invoked here as the example they are all following. However, this analogy is fraught. Amazon is truly a once-in-a-generation company, if not more rare. A combination of relentless focus on the customer, extreme capital efficiency and entrepreneurialism have combined to create a remarkable enterprise.

For context, Amazon raised money twice before its IPO. In addition to start-up funding from his parents, Jeff Bezos raised ~$1m from 22 people in 1995. He then raised $8m from Kleiner Perkins as the last major raise pre-listing. Venture-backed companies comically claim to be the ‘Amazon of X’. What they are actually saying is ‘we want to be just like Amazon in terms of scale, focus and efficiency, but we realize we’re nothing like that company, so we need to raise hundreds of millions of dollars to even have a chance’.

For what it’s worth, to call yourself the Amazon of anything shows a fundamental misunderstanding of Amazon. Amazon is not necessarily a single company, but rather an entrepreneurial engine that shifts and adapts to whatever its customers demand. Raising enormous rounds can be a death sentence for companies who really need to retain the ability to pivot through their growth and remain responsive to feedback, not quadruple-down on what it is they think they are in year three. Had Amazon raised a mega-round in the late 90s, we likely would never have seen Amazon Marketplace or AWS.

The analogy to Amazon is therefore at best dangerous, and at worst, delusional. The odds are not in the favour of many of these companies; becoming another Amazon is not a winning strategy. Having said that, some of them will succeed and deliver on their vision. What many of them have achieved is incredible — I truly commend their founders and the vision of early investors that provided them the opportunity to get where they are. However, someone will eventually be left holding the bag, and it’s worth considering who that will be and what it says about relative values.

The importance and relevance of asymmetry.

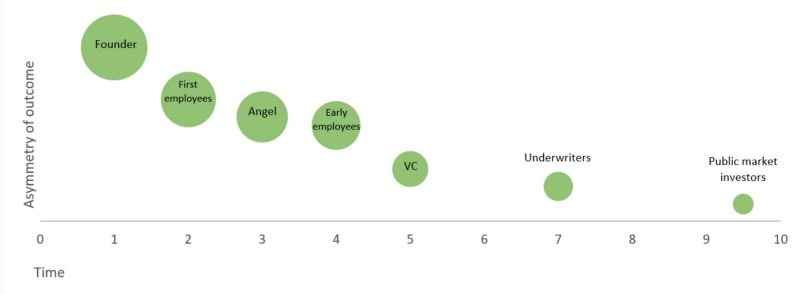

The chart below attempts to show the relationship between time and the asymmetry of outcome, in an investment sense (time and/or capital), for different participants in the journey of a growth-at-all-costs company. The asymmetry — the potential upside relative to the downside — is clearly higher the earlier in time you invest. The size of the circle represents the magnitude of the potential upside should a favourable outcome accrue. It’s rough and imperfect, but hopefully illustrates the point.

To get started, the entrepreneur’s greatest investment is of her time, assuming the venture is not capital intensive in its early stages. If a year or three down the track the venture remains unsuccessful, the entrepreneur has lost her time, which includes significant opportunity cost. If she is successful, the potential upside is considerable. This is the asymmetry. This chart does not consider the likelihood of a favourable outcome, just the asymmetry. Despite the low likelihood of significant financial success for most entrepreneurs, the magnitude of the prize is the carat.

Those who take on the required level of personal risk should absolutely be commended, and the rewards for taking these risks are generally justified. We should all seek out asymmetric opportunities in our careers, so I am not disparaging this path or outcome. What I am seeking to do is clarify where the greatest value accrues in such a company’s evolution and how incentives will develop accordingly. More on this shortly.

Assuming that these ventures continue to hit some growth-centric metric, existing and new investors pile in with cheap capital and higher valuations, marking up the value of each early investor (founders, early employees etc. are included in this definition, as they are investing their time). Achieving a misguided growth metric is seen as a green light to continue the onward march to market dominance and the profitability it entails.

The question for me is why late-stage institutional (generally private) and public market investors continue to pour capital into ventures with such strong prospects for perpetual loss-making? Per the above, the asymmetry of their outcome is diminished given their later entry point. One answer is that the availability of cheap and abundant capital for 10 years has created an endless search for returns and associated bubbles. This probably explains the institutional side, but what of public market investors? What narrative are they pursuing?

Who does growth-at-all-costs really benefit?

The intent behind the chart and the discussion above is to show that the growth-at-all-costs venture-funded journey is optimized for value accretion for those that are early, not for building a sustainable business. All one needs to do is look at where and how value accrues to understand why those who stand to benefit the most may push a particular narrative.

Those who stand to win big, absolutely have a vested interest in pushing the narrative that growth-at-all-costs (at the expense of profitability) is divine. This includes venerated-founders (see below), angels and VCs. They ‘win’ because they were early. Wins ensure that venture funds can continue to raise ever-larger funds and live off their ballooning fees. When they need to figure out what to do with their comically-outsized warchests, marking-up their own earlier investments is the logical move. There is a circularity to the venture fund’s value accretion. Marking up their own investments and deploying growing amounts of capital provides the platform for their most important next step: raising another, larger fund.

The value of growth is therefore relative. It is being held up as an absolute value, but it’s being held up by those who stand to benefit the most from its celebration: founders and early investors. We have become enthralled by the founders and investors pushing the growth-at-all-costs narrative but have neglected to consider that they are ones who profit the most from this narrative. We should be taking the narratives they push with a very large grain of salt.

Unfortunately, the way we fetishize Silicon Valley and venture in general means that these people are the loudest with the biggest platforms and megaphones. The media, beholden to ad spend, dutifully amplify this bullshit in the pursuit of endless content. Scott Galloway may have said it best:

I believe our society is effectively going through this very uncomfortable transition that is bad for our youth, bad for America and bad for the planet where we no longer worship at the altar of character and kindness. We worship at the altar of innovators and billionaires.

As a society, we have idealized the founder, notwithstanding his or her clear limitations. Disappointingly, we have handed over the keys to this part of the economic narrative.

The question then becomes, so what?

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with creating immense wealth for founders and investors if they create great businesses and companies. But if my characterization is correct, they’re not building great businesses. They’re building unsustainable cash-burning vehicles optimized for creating value for early investors and participants.

To my mind there are a number of downsides to this:

The biggest potential losers in this journey are employees and public market investors. Employees will typically receive a moderate salary with a greater emphasis on stock options. To the extent these options are worthless (due to a collapse in valuation) or remain illiquid, employees suffer potentially life-changing consequences. Their plans are thrown in disarray.

Venture capital investing has become based on ‘belief’, ‘theses’, ‘narratives’ and ‘individuals’ (just look at WeWork’s S-1 filing where the CEO is actually listed as a risk factor). An enormous amount of capital has been wagered on the belief system remaining intact. We are late cycle by anybody’s measure, and when the turn comes, venture funding will dry up, along with the hopes of hundreds of companies and thousands of high-paying (or stock-based) jobs. Founders and early investors have already made their money and will likely have cashed out by then, and as mentioned in #1, employees may be left holding the bag.

Late-stage private (which is actually now public funds) and early-public market investors buy these companies at the highest possible valuation, with no prospects for a slowdown in capital requirements. Some are structurally unprofitable businesses who without further cheap cash to burn, are post-growth. They buy with asymmetric downside.

We are breeding a culture of capital ill-discipline. Where capital is this abundant and the concern for how it is spent so absent, we create absurd expectations that it will always be this cheap and available. We are undermining the worthwhile challenge involved in building thoughtful, sustainable businesses, by simply throwing money at these ventures.

Building on #4, we are breeding a workforce that has no regard for budgets. The very bright and ambitious young people who make up the workforce of these companies have very rarely considered the concept of a ‘budget’. Well, they have, but only on one side of the ledger. Where growth is the ultimate goal and metric, it doesn’t matter what it costs to obtain that growth. Whether it’s paying irresponsible multiples for assets, insane customer acquisition costs, or even attracting the best talent with premium office space, we are doing a disservice to a very promising cohort of people by not teaching them about “business”.

My hope is that this piece is viewed as a useful tool for interpreting what we are being force-fed around growth and venture investing. As with most things in life, we must look at where and how value accrues, and understand how those with the loudest voices are incentived to push a particular narrative.

We must continue to have lucrative benefits in place for those who take the necessary risks required to build something great. But we should ensure that their incentives are aligned with building something sustainable, not just the modern version of the get-rich-sort-of-quick-but-mainly-through-gaming-the-cap-table scheme. All cycles eventually turn, and when this one does, hopefully this piece provides a reminder of where we may have gone wrong.

I’d like to finish with a comment on Amazon. It is a business optimized for its customers, however and wherever they wish to transact. The relentless focus on delivering what its customers want is the secret to its success, and incredible focus on intellectual consistency and excellencec is the secret to its execution. Market dominance flows from doing a phenomenal job, not by throwing endless amounts of capital at something. A system optimized for this outcome will deliver better long-term shareholder and consumer outcomes. Let’s aim for that.

—

Note: This piece was originally drafted in the lead-up to Uber’s IPO and was finalized following WeWork’s IPO filing. Since then, Adam Neumann has been forced out as CEO, the IPO has been delayed indefinitely and Softbank and its stable of investments have come under greater scrutiny. In the aftermath, public markets have forced late-stage venture investors and large venture-backed companies to reflect on the “growth at all costs” mindset, especially for those companies that are not steady-state high gross margin businesses. I believe this piece takes on greater significance in light of recent events, as it provides a guide for understanding how we got here, and where we may go.